The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Robert Fisk: 'We remain blindfolded about Isis' says the man who should know

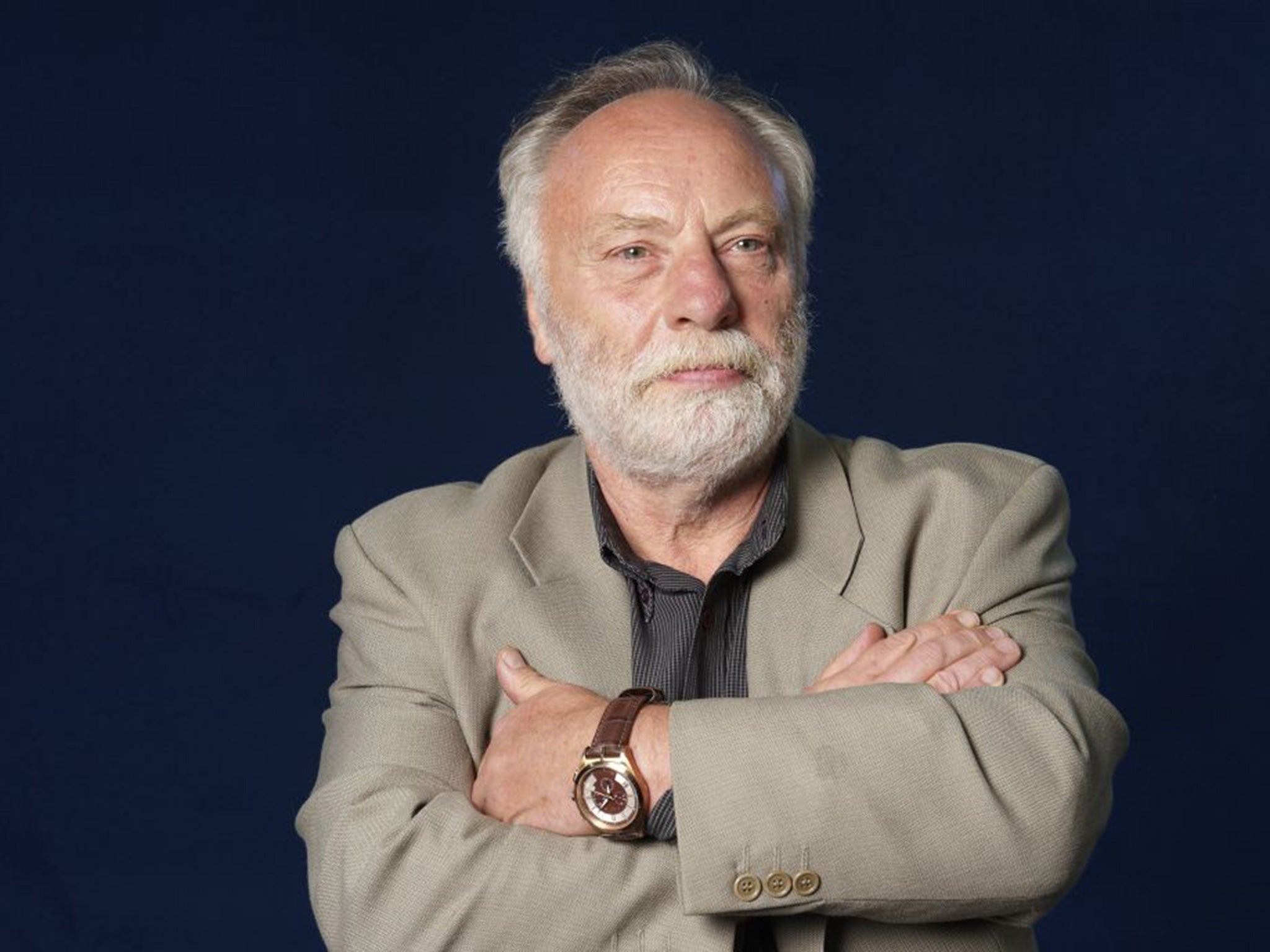

Brian Keenan was held by Shia Muslims loyal to Hezbollah in Lebanon

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

With atrocities in Sinai, Beirut and Paris (and let’s keep the order in sequence here, since all those lost innocents, Russian, Lebanese and French, are equal as our brothers and sisters), I was beginning to think that our emotions were becoming as insane as the perpetrators of these crimes. An “act of war”, a response “without mercy” – the French response was straight out of the Isis vocabulary.

So immediately after the Paris massacres, I sought for reason, clarity and wisdom from a man who spent four and a half years in the hands of Muslim kidnappers – 54 months wearing a blindfold, always waiting for death.

Brian Keenan was held by Shia Muslims loyal to Hezbollah in Lebanon. Had he been taken by Isis in Syria or Iraq, we would by now have been able to watch his beheading on video – yet he kept his sanity to write the only literary work to emerge from a Western kidnap victim of Beirut in the 1980s, An Evil Cradling, a book that will live for a hundred years as a monument to humanity amid suffering.

It doesn’t take much of a commitment to kill people. What happened doesn’t surprise me.

Keenan sipped his coffee in rainy Westport in the far west of Ireland – he was born in Belfast – and spoke slowly, almost philosophically. He rarely gives interviews. The Paris slaughter had happened only 16 hours earlier. “The contagion has broken out of its confinement,” he said. “Someone has planned all this for a long time. There is a lot of organisation – but it doesn’t take much of a commitment to kill people. What happened doesn’t surprise me. What surprised me was that what happened in Beirut [24 hours earlier] spun to Paris. It’s as if the culture of victimhood which is rife in the Middle East … has risen to new levels, legitimising the worst horrors.”

It’s not difficult to see that Keenan’s own experience slides imperceptibly into his arguments, giving them an elliptical quality as well as a frightening immediacy. He talks as if he is still confined in a Beirut cellar.

“What do we need to do about this? In a global dimension, we all have to take some responsibility for this. My own thoughts – after four and a half years in captivity – is that the dispossession and the anger has to be acknowledged. These people have to be offered something more than revenge or Holy War or even this perverse Islamic apocalypse. I’ve seen too many times the map of the Middle East changing – many borders are irrelevant now.

“What worries me is that as these old borders and ‘international zones’ disappear, ‘security barriers’ become the new borders. We’ve seen this in the Middle East and they are rapidly being erected across Europe. These worry me more than the term ‘terrorism’. They create these kinds of conceptual contours – it’s not just a wall, it’s a wall that defines a lot of cultural beliefs and misbeliefs. We are damaging ourselves with these walls – we are damaging our ability to think, our ability to be creative.”

Keenan is a hard man. He has returned four times to Lebanon – on his own – since he was released by his hooded kidnappers, to discover what he calls “the stories lying about on the streets of Beirut if you just pick them up”. It’s a phrase used by the Lebanese writer Elias Khoury, who insisted that there was more than just one narrative – the Israeli story – about the Middle East, and it led Keenan to return to those who were behind his kidnapping. To understand all this, he thought, “was the debt Lebanon owed me”.

So he feels extraordinary sympathy with those who lost their loved ones in Paris. “I acknowledge their right to be angry,” he said. “Even to put no restraint on their anger. But my own feeling is that anger can be healing if you use it in a meaningful way. Elie Wiesel has written of how he came back from the concentration camps full of anger – but he turned that into something creative.

“It’s not easy. He talked about the panacea for anger and violence – he said that a country that does not build on a foundation of love will ultimately wither away with the poison it feeds off.”

I’m about to tell Brian Keenan that all this is a bit flippant after an airliner has been blown out of the sky and a Beirut crowd blown to bits and 129 French citizens blasted and machine-gunned to death, all in two weeks, when he put a finger in the air. “Part of the problem with the Middle East,” he said, “is that war is diplomacy. That’s at the root of how you ‘justify’ and ‘meaningfully’ deal with the problem.

“The other thing to ask is: who are the war criminals? There’s a kind of skewed vision of what a war criminal or a war crime is. We need to honestly think about this if we are going to talk about justice – so that everybody feels that justice is being done. If the Nakba [the expulsion of 750,000 Palestinians from their land by Israel in 1948] has now gone global, we need a different set of principles. I don’t know that people are ready to make that profound self-examination.”

I’m not sure that Isis cares about the Palestinians – Isis burned the Palestinian flag because it wanted a caliphate, not another national state – but Keenan talked about something far deeper.

“I wore a blindfold for four and a half years, and ‘Western democracy’ tells me that justice is blind. I’m not sure about this – because until we can un-blindly question how power is dispensed, then we’re all wearing blindfolds.”

The Hollandes and Camerons and Obamas of the world will not read these words, of course. Emotion, not reason, is the policy option. “Without mercy” is now our dogma as well as that of Isis. Which is why Isis is winning. But I guess you need four and a half years in a blindfold to understand that.